Recent developments have cast new light on the issue and energized advocates trying to end the practice. Last February, 2014, President Obama issued an Executive Order that raises to $10.10 the hourly minimum wage paid for work performed by parties who contract with the Federal Government, including workers with disabilities. According to the Order, raising the pay of low-wage workers increases their morale and the productivity and quality of their work, lowers turnover and its accompanying costs, and reduces supervisory costs.

|

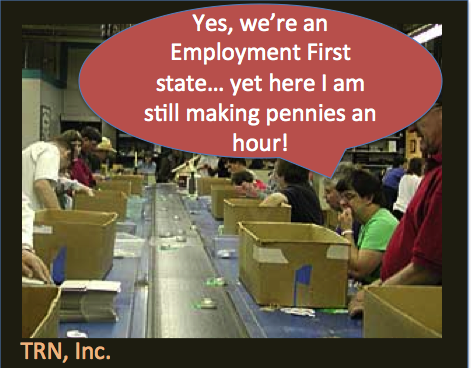

| Photo credit: APSE |

Yet, at the same time, SourceAmerica, formerly known as NISH, as the agency responsible for distributing government contracts to non-profits, continues to routinely award such contracts to many non-profits that pay workers with disabilities less than minimum wage. Indeed, it has even lobbied against the phasing out of Section 14(c). This recently lead to a very public protest of SourceAmerica headquarters by a collaboration of national advocacy organizations, including APSE, the National Federation of the Blind, the National Council on Independent Living, ADAPT, Little People of America, and TASH.

Finally, bi-partisan support continues to grow for US House Bill H.R. 831, The Fair Wages for Workers with Disabilities Act. Now with 96 co-sponsors (as of August, 2014), the bill would end issuing any new special wage certificates by the Department of Labor. It also phases out existing certificates, giving for-profits one year until their certificate is revoked; public entities have two years; and private non-profit vocational providers using sub-minimum wage will have 3 years to transition to integrated job placements at commensurate wages. At that time, Section 14(c) of the Fair Labor Standards Act will also be repealed.

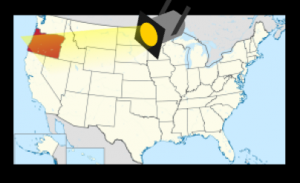

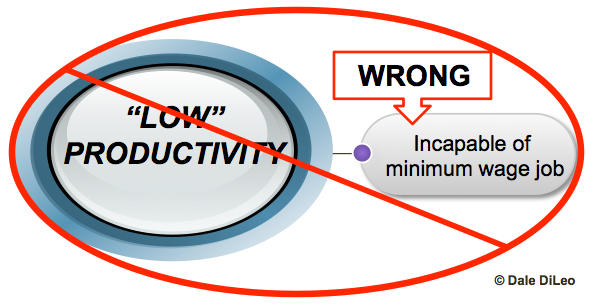

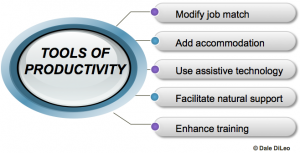

Over 2700 existing certificates are being used across the US currently. Predictably the outcry from most in reaction to the pending legislation has been dire predictions of layoffs, closures, and the spectra of people having nowhere to go or nothing to do. And while this could actually happen, it could only occur if those providers elect to do nothing about modernizing their services over the phaseout. In fact, there are many other agencies that exist that serve the same individuals with the same kinds of support needs, and do so without using sub-minimum wage. A good deal of evidence supports the ending of this antiquated practice.

It’s time to make US wage policy consistent and inclusive of all people, including workers with disabilities.