If you are unfamiliar with the term “ableism”, it is a word, much like racism, that describes a societal condition that leads to the widespread discrimination and segregation, but in this case focused on those with a disability label.

If ableism describes the culture that subjects people with disabilities to rejection, how do we analyze a service system that tries to help people, but in doing so, ends up reinforcing ablistic values of the culture? This is something I call “benevolent ableism.” when well-meaning people set up programs or services that also segregate or send messages of stigma due to using disability as the defining core of the services, rather than such things as individualism, quality of life, informed choice, and inclusion.

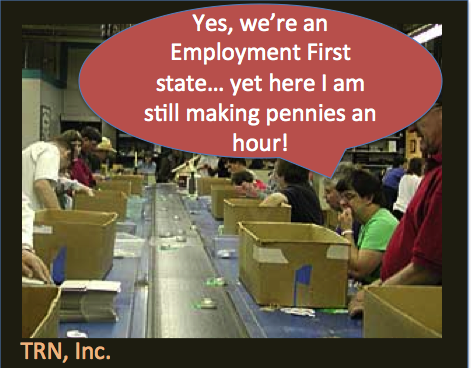

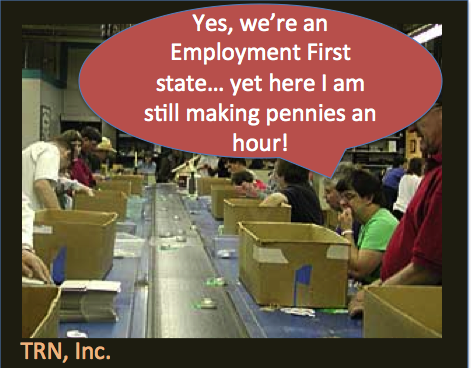

Historically, we have seen benevolent ableism in the development of sheltered workshops, group homes, and day activity programs, which were touted as the alternatives to institutionalization, which itself was considered a benevolent service of its time. Unfortunately, all these models, while offering an option instead of something worse, still kept people from experiencing the kind of life they deserve.

The challenge of benevolent ableism is that those who perpetuate it are well-meaning, caring folks who feel their actions are improving the lives of people with disabilities. But, unfortunately, efforts to help do not automatically equal actual improvement of lives. What are the problems?

1. Helpers Have More Power than their Recipients

Those who help hold all the cards; that is, disability service professionals and not those in need of support, mange the funding, call the shots and make the rules.

2. Helping Programs Arise from Prevailing Disability Service Fashions

Various disability service models have come in vogue over the years, and what is popular often determines what form the help will take. Sometimes what is popular has been poorly researched, if studied at all, and not held to any level of accountability. For example, studies have produced no evidence that time spent in sheltered workshops helps the employability of people with disabilities. In fact, the opposite is true.

3. Helpers Can Succumb to a Rescue Mentality

Those who help, regardless of how well-intentioned their motives, can easily take on the role of savior and protector against all others. This dampens their ability to hear genuine criticism, insulates their approach, and at the same time, places the people being assisted as helpless without their rescuer. The rescuer will often have the individual being helped follow a path that leads to dependency rather that self-sufficiency.

In the end, benevolent ableism is often at the root of what is keeping those who mange models that segregate and isolate people with disabilities from changing what is obsolete. The rescue mentality, the resistance to innovation, and the self-serving “we know what’s best” is ultimately preventing people with disabilities from more individualized supports that could lead to more inclusive lives in our communities.

If the disability field is to support the quality of life for people, we must realize that the concept “quality of life” can be a very elusive and varied goal for each individual. We should all, including those of us who are advocates for change in the existing system, have an openness to hear views that challenge our thinking. After all, if we are to escape benevolent ableism, we could all use a little more humility in our efforts to help.