Over the last few years, the Employment First (EF) movement has taken off in nearly every state and several Canadian provinces. The clear intent of an EF movement is to make an individual, integrated, paid job the first option for individuals with disabilities receiving day services.

Over the last few years, the Employment First (EF) movement has taken off in nearly every state and several Canadian provinces. The clear intent of an EF movement is to make an individual, integrated, paid job the first option for individuals with disabilities receiving day services.

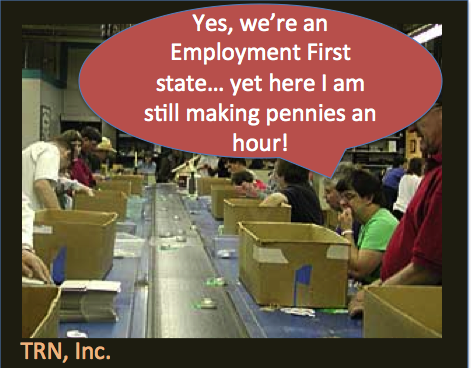

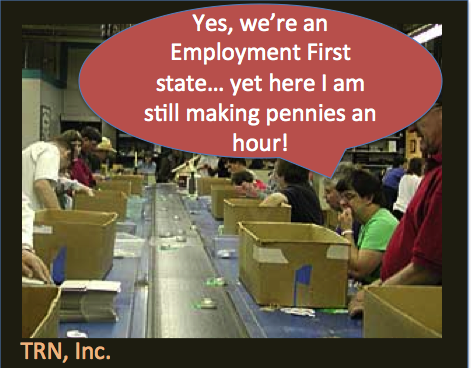

This is no easy task for a service system that relies on segregated facilities. The context is that only 21 to 23% of people served in day services are currently employed in the community. A good number of those individuals are in group employment settings such as enclaves and crews. Most individuals with disabilities of working age find themselves in sheltered workshops, or non-work community day programs.

In addition, there remains a steady reliance on sub-minimum wages in both sheltered workshop placements as well as in some supported employment services.

For EF to succeed, it must not only change expectations about individuals with disabilities and employment; it must fulfill those expectations with results. The devil is in defining what those outcomes should look like. Having now worked in numerous states and provinces struggling with implementing or beginning an EF approach to services, here are some priorities about what success should look like, and how to overcome some of the obstacles traditional services present:

Goals

It is not enough to measure the number of new placements made since implementing EF. You also must expect a decline in facility-based workshops and non-work programs at the same time. Ultimately, systems change should be reflected in a greater ratio of people in individualized integrated work versus workshop/non-work programs. Citing greater numbers of placements has little meaning when the numbers served in the day system itself are growing, sometimes at a greater rate than the rate of increase in employment.

Using sub-minimum wage to solve productivity issues in employment is unnecessary and a shortcut that avoids using better job matching, accommodation, training and other support strategies. It also has been shown to open people up to exploitation, and causes a continuation of impoverishing already marginalized people.

Letting young people and others enter an obsolete system that has caused a movement toward EF is unconscionable. In public policy, one should never needlessly inflate a system you are trying to devolve.

Overcoming Obstacles

Having people re-enter a facility perpetuates a continued reliance on segregated services during non-work or non-employment periods, when the focus should be on re-employment, community job skill training, career development or seeking greater hours.

Without ending workshop referrals, workshops will continue to segregate and serve individuals needlessly, despite clear evidence of poorer outcomes for the individual and lower cost-benefits to the taxpayer.

When you define the problem as simply closing workshops, you end up with a lot of people volunteering, shopping or hanging out. This is neither the goal nor a solution to segregated employment.

~

EF has caused great fanfare in many places, and we have seen a number of pronouncements and proclamations. But will we see the system actually change its outcomes? Let me know what you are seeing in your part of the world. Let’s not be disappointed with the opportunity EF represents…