[Jewish, Italian, African-American, etc.] and [live, work, play] with people with my same label.”

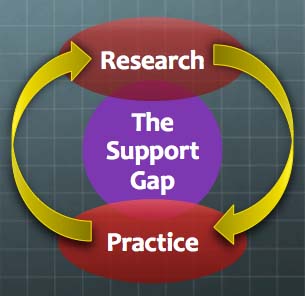

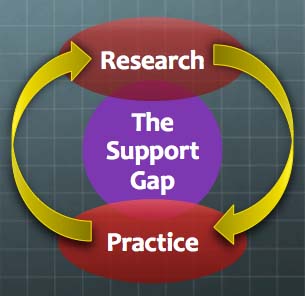

Good points, but these arguments miss the mark. They represent a kind of binary thinking (disability groups are bad/good) that is all too common. They oversimplify social grouping, which is a sophisticated sociological phenomena. Understanding how groups function is a key to successful individual community life as well as personal self-worth.

Groups can provide important social cohesion. This can be very positive for when an individual wants to validate his or her social identity, or share experiences with people who have some commonality. For a repressed minority group, it can be particularly important. A person can establish self-identity and take pride in it. In-group members relate with others who have shared experiences and cultural expression. Group members can form a basis for friendship, and advocacy of the shared commonality. Indeed, many people who are deaf, or who have dwarfism, for example, express strong preferences about living among others with the same life situation for a variety of reasons. And peer support groups for persons with mental illness have been shown to be helpful for group members.

But the difference on making an educated decision to voluntarily join a group for social cohesion, support, or advocacy, versus having a group experience imposed on you is huge, especially in regards to individuals with disabilities. People benefit from having a range of social experiences and participating in groups defined by different gathering reasons, and then being able to make educated choices about how they want to experience their communities.

There is also an important social perception issue related to disenfranchised groups in which the group members are subject to negative stereotypes. What happens is that when an individual is seen as part of a group, the group commonality becomes prominent and defining. This leads to sociological issues when the commonality is not particularly valued, including prejudice and bias, intergroup hostility, and discrimination.

Group definition plays out in the context of how providers organize services. If you have a certain “functioning level,” or a label such as autism, behavior problem, intellectual disability, etc., your service experience will likely be more defined by that characteristic, rather than by your personal life needs (job, home, etc.). While a “treating-the-problem approach” is common in a medical model, it produces a severely limiting life experience for someone with a disability. They become “boxed in” by perceived and potentially misunderstood disability and support needs in terms of employment, housing, recreation, and more. Not only that, but individuals with disabilities often find themselves surrounded by others with the same disability or “level of function,” limiting access to others who might mentor, model, or perform at a higher level.

Fully understanding how to make good decisions about what groups to be a part of, in what context, and for how much of one’s life is a big decision people must make. Whom do I live with, what kind of work do I do, whom do I have fun with are major questions for us all. What professionals shouldn’t do, though, is track people into pre-made groups as answers to these questions based on their disability label. This ultimately limits the answers to those models that disability professionals have artificially created.

So, consider the kinds of questions we ask:

- It’s not: What disability work crew you want to join?; It’s: What kind of job do you prefer?

- It’s not: What group home you want?; It’s: How do you want to live and with whom?

- It’s not: Do you want to go to the mall with other people from your residential placement?; It’s: What do you want to do for fun and with whom?

And remember, if all your previous experiences have been defined by group homes, workshops, crews and enclaves, and all your friendships have developed from group home co-residents placed by others, then saying your current situation is your “preference” is really not choosing at all. When someone understandably selects the only thing they have known, then we have failed to support him or her in understanding all the possibilities.