How often do we see it when we look back at our work year? Task forces created, planning groups assigned, attending meeting after meeting, writing goals and objectives, action plans, giving assignments, and then… and then… We look back, and then look around, and we notice that things are not really that different. It’s the Perpetual Planning Syndrome.

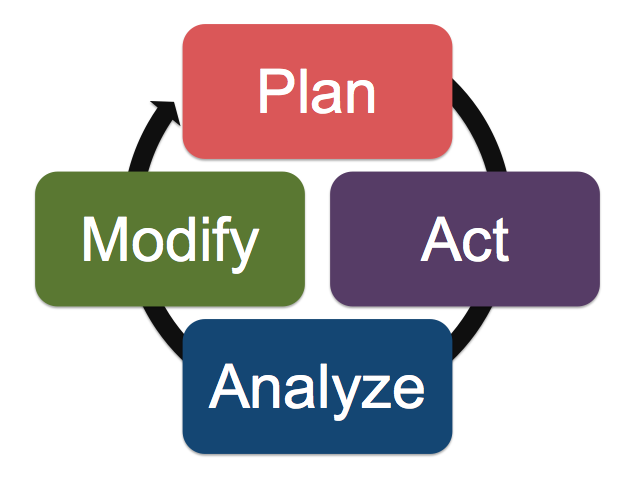

Planning, with all its complexities, still has one purpose. And that is to make the things we DO – the actions we take – for ourselves, our agencies, and others, more efficient, effective and meaningful. That’s because haphazard actions to try to change or create new services can lead to unintentional outcomes that can be wasteful or even harmful.

In fact, the greater the complexity of the action, and the more significant its impact, the more thoughtful planning is needed. For example, transforming an agency from a facility-based model to a customized community-based approach requires thought and sensitivity. You should have clear strategies for engaging stakeholders, stabilizing funding, building your service capacity, and downsizing your reliance on a facility. But should a clear plan take endless meetings and years to accomplish? Not at all.

You don’t need to define every aspect of every possible situation to evolve a service. And a main reason is that each step taken toward your goal will lead to new information. In addition, you will likely experience new and different circumstances than what you anticipated. The longer the timeline goes out, the less valid will be the strategies you are making plans for now.

To start, always have a clear idea of what your ideal end point will look like – this is important so that you just don’t keep chasing new ideas because it’s the latest hot idea. Know your vision then figure out what initial steps you need to take within the first 6 to 12 months that will get you committed to the real innovation and change that meets your mission. Once you accomplish these, review your end goal to be sure it looks the same, and then figure out where you need to go next, based on what you learned and where you are now. Get some advice from people outside your frame of reference, who can dispassionately tell you what is working and what isn’t.

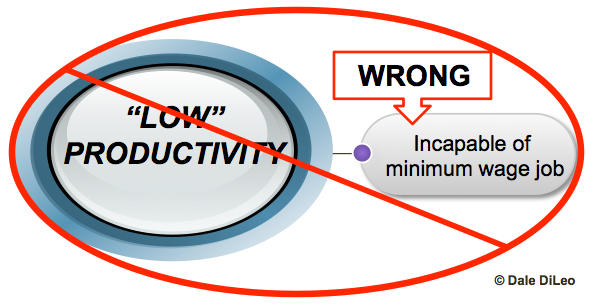

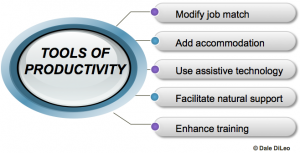

By the same token, this is true on an individual level. For example, if career planning and the Discovery Process does not lead to a quality job for someone, then all the strategizing has been besides the point. Don’t confuse the goal for the tools you use to help get you there. Doing Discovery is not a goal. You are no closer to a job with a Career Plan, unless it is actually used to find a good job match.

The goal is a job, not a plan. Or, for an agency, the goal are people in good jobs and not workshops. Making a plan does not get you started; it’s only a preliminary road map. What gets you started are taking the actions you’ve thought about and then making successful outcomes. Time is important. Many people with disabilities have spent lifetimes without opportunities to experience life in the way most of us take for granted. Excessive planning wastes time, and lives are wasted while professionals meet.

Yes, a road map is useful to get you to where you want to go efficiently, but it’s taking the actual steps that count.