Several issues reside in the heated discussions over the need to change the traditional day service model for people with disabilities. But the defining one relates to competing beliefs about productivity:

Can individuals with the most significant disabilities be productive in the workplace, such that sub-minimum wage is unnecessary?

- “Would you hire somebody who is working at 30% and not meeting productivity goals?”

- “What if somebody is not capable with or without an accommodation of working at a regular job? Should we force them into a rehabilitation program with no work or sit at home and watch TV?”

- “If you eliminated 14(c), you would lose the opportunity for these people to be trained to be employed.”

A number like that put on a person is damaging; it is just an arbitrary label like any other stereotype.

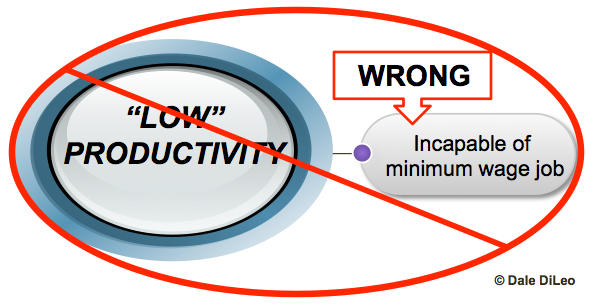

The assertion that removing sub-minimum wage will lead to job loss is not only unproven, but false. This is demonstrated by the many workers across the US with very challenging disabilities who are working at minimum wage or better, yet whose productivity ratings in traditional (segregated) work training settings were extremely low. It also sets up a false choice (i.e., low paid work or none at all). This kind of thinking is only true if you have a narrow (and I would argue obsolete) view of job placement, productivity, and what people are capable of.

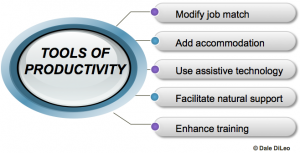

Here is the missing piece: The best predictor of job success is not whether we can convince employers to let people work at lower standards for lower wages; it is how well we customize employment and provide job supports to meet productivity demands. It is inherently unfair to close perceived productivity gaps by reducing the wages of those who need money the most, especially when we have other proven tools to enhance productivity.

The continuing use of sub-minimum wage is actually hindering our ability to promote and provide well-matched employment. It has become an obstacle, first because of its misuse (the ongoing documentation of many instances of low wage exploitation alone should cause it to end). And secondly, because it has caused providers to rely on a “low cost” plea for job placement, rather than investing in the real task of developing the skills job developers need to produce a more productive job situation.

Productivity, at first glance, seems to be just a matter of how fast you do what is given to you. But dig deeper, and you see that is more about how well the worker is matched and supported to accomplish something needing to be done. And the answer on succeeding in that, though challenging, is up to the provider’s abilities at customizing, accommodating, carving, training, and more.

Lobbyists for day programs hanging on to sub-minimum wage as an answer for their belief about those “not capable of work” need to rethink the message they are giving. “He has 30% productivity” is no better than any other discriminatory disability stereotype, and it flies in the face of federal law where there is a presumption of employability. And it’s a damn shame that Senator Harkin has accepted it as fact.