Over the last few years, the Employment First (EF) movement has taken off in nearly every state and several Canadian provinces. The clear intent of an EF movement is to make an individual, integrated, paid job the first option for individuals with disabilities receiving day services.

Over the last few years, the Employment First (EF) movement has taken off in nearly every state and several Canadian provinces. The clear intent of an EF movement is to make an individual, integrated, paid job the first option for individuals with disabilities receiving day services.

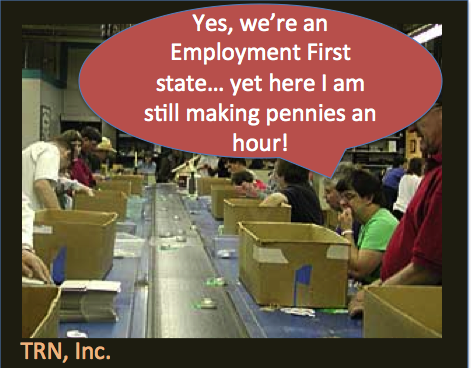

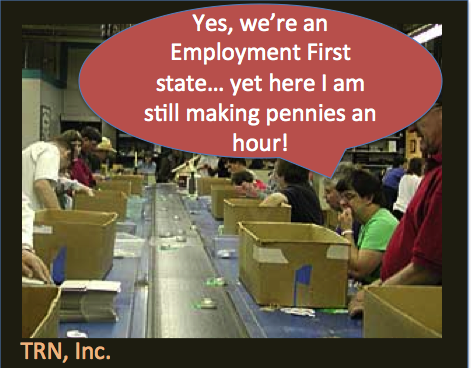

This is no easy task for a service system that relies on segregated facilities. The context is that only 21 to 23% of people served in day services are currently employed in the community. A good number of those individuals are in group employment settings such as enclaves and crews. Most individuals with disabilities of working age find themselves in sheltered workshops, or non-work community day programs.

In addition, there remains a steady reliance on sub-minimum wages in both sheltered workshop placements as well as in some supported employment services.

For EF to succeed, it must not only change expectations about individuals with disabilities and employment; it must fulfill those expectations with results. The devil is in defining what those outcomes should look like. Having now worked in numerous states and provinces struggling with implementing or beginning an EF approach to services, here are some priorities about what success should look like, and how to overcome some of the obstacles traditional services present:

It is not enough to measure the number of new placements made since implementing EF. You also must expect a decline in facility-based workshops and non-work programs at the same time. Ultimately, systems change should be reflected in a greater ratio of people in individualized integrated work versus workshop/non-work programs. Citing greater numbers of placements has little meaning when the numbers served in the day system itself are growing, sometimes at a greater rate than the rate of increase in employment.

Using sub-minimum wage to solve productivity issues in employment is unnecessary and a shortcut that avoids using better job matching, accommodation, training and other support strategies. It also has been shown to open people up to exploitation, and causes a continuation of impoverishing already marginalized people.

Letting young people and others enter an obsolete system that has caused a movement toward EF is unconscionable. In public policy, one should never needlessly inflate a system you are trying to devolve.

Having people re-enter a facility perpetuates a continued reliance on segregated services during non-work or non-employment periods, when the focus should be on re-employment, community job skill training, career development or seeking greater hours.

Without ending workshop referrals, workshops will continue to segregate and serve individuals needlessly, despite clear evidence of poorer outcomes for the individual and lower cost-benefits to the taxpayer.

When you define the problem as simply closing workshops, you end up with a lot of people volunteering, shopping or hanging out. This is neither the goal nor a solution to segregated employment.

~

EF has caused great fanfare in many places, and we have seen a number of pronouncements and proclamations. But will we see the system actually change its outcomes? Let me know what you are seeing in your part of the world. Let’s not be disappointed with the opportunity EF represents…

Over the last year, I’ve been in front of numerous audiences to discuss the concept of Employment First and the need to phase out facility-based sheltered workshops. I don’t make the argument lightly. It is a wholesale change of focus for many. It uproots individuals from their comfort zone. It is threatening to agencies and parents. It requires funding and core policy shifts.

But regardless, I find that most of those who refuse to make changes to a sheltered work system simply aren’t listening. They don’t want to examine evidence, because they see no need to change what they are comfortable doing. The threat of change, and the likely corresponding difficulties that go with any change, are too troublesome.

But regardless, I find that most of those who refuse to make changes to a sheltered work system simply aren’t listening. They don’t want to examine evidence, because they see no need to change what they are comfortable doing. The threat of change, and the likely corresponding difficulties that go with any change, are too troublesome.

This week, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) reached a landmark settlement based on the conclusion that the state of RI and the city of Providence failed to provide services to individuals with developmental disabilities in the most integrated setting, and were putting students in a school transition program at risk of unnecessary segregation in sheltered workshop and day program settings. Earlier this year, DOJ had investigated the state for violating the Olmstead decision of the Supreme Court through its day activity services system. They focused on Training Through Placement (TTP), a North Providence agency that had a sheltered workshop with transitioning students from the Birch Vocational Program and other schools.

Under the settlement, individuals in Birch and the TTP workshops will now receive supported employment and integrated day services sufficient to support 40 hours per week. It is expected people will work an average of 20 hours a week and receive competitive wages. According to the agreement, supported employment placements cannot be in sheltered workshops, group enclaves, mobile work crews, time-limited work experiences (internships), or other facility-based day programs.

Under the settlement, individuals in Birch and the TTP workshops will now receive supported employment and integrated day services sufficient to support 40 hours per week. It is expected people will work an average of 20 hours a week and receive competitive wages. According to the agreement, supported employment placements cannot be in sheltered workshops, group enclaves, mobile work crews, time-limited work experiences (internships), or other facility-based day programs.

The 29-page agreement is quite comprehensive, and follows on the heels of another DOJ intervention regarding sheltered workshops in Oregon (see The Good, Bad and Ugly). This now marks two separate states that within the last six months have been pushed, under the Olmstead decision, into finally taking action against their long-standing policies of primarily funding sheltered workshops for day services. Clearly, the issue of day service segregation is finally moving from “wait and see” to civil rights enforcement.

Let’s look at the Rhode Island situation further. TTP workers with disabilities made an average $1.57 per hour, with one person making as little as 14 cents per hour. The investigation also found that Birch students were generally denied diplomas. Most were paid between 50 cents and $2 per hour, or were not paid at all, regardless of productivity. DOJ noted that the Birch program had been in existence for 25 years, and was a “direct pipeline” for cheap labor for TTP, which had contracts with local companies. The jobs were mostly typical of sheltered workshops, assembling jewelry, bagging, labeling and collating.

Effective March 31, 2014, the State will no longer provide placement or funding for any sheltered workshop or segregated day activity services at TTP. Further, last March, Rhode Island embraced an Employment First policy. Under the new policy, new participants in the state system that provides employment and other daytime services to 3,600 people with developmental disabilities will no longer be placed in sheltered workshops. The sheltered workshops should be completely phased out within the next two to three years.

The next question that should come to mind, if you are running or funding a program in a state chock full of workshops, is “Am I next?” Readers of this blog can examine the case presented for moving away from sheltered employment in other posts here. I also have had this discussion with some of the US DOJ attorneys. It’s time to expand the Employment First movement so that we away from sub-minimum wage, segregation, and limited work options, based on an obsolete model that can leave people open to exploitation. People with disabilities deserve better in every state. Employment First should not just be rhetoric. Take a leadership role now; there is no reason to wait for a lawsuit…

I’ve known Cary Griffin for over twenty plus years. He has been an extraordinary consultant and trainer in the disability field, and I have always considered him someone I could bounce ideas off of and get an honest answer.

As always, we invite respectful comments – I look forward to reading your reactions.

Have a wonderful holiday season, everyone, and, (wherever you do it!) thanks for all that you do.

Employment First presents a great opportunity, but there is a real concern that new employment initiatives, while well-intentioned, will be developed incompletely and ultimately again will do little to change a largely segregated and entrenched vocational system. That would be a tragedy.

We must avoid having Employment First go through a process of misunderstood implementation, leading to an all-too familiar conclusion about new innovations that are perceived as being attempted and falling short, or “We tried that and it didn’t work…”

TRN has released a new manual on this topic that I authored. Most likely the most challenging point of this manual on Employment First is its position to publicly acknowledge that the segregated nature of much of the disability vocational training system to date has not only failed to produce good job outcomes for people with disabilities, but also has acted at times as an obstacle to people with disabilities leading fulfilling lives. Facility-based sheltered work has been a barrier by adding stigma to its workers, paying predominantly sub-minimum wages, and wasting time and resources that could be spent in actual employment. In addition, service components of much of disability job training, such as intrusive behavior management, labeling, and other artifacts of the human services system, have created further barriers to job success.

Politically, many agencies, including national associations, have tried to focus on growing integrated services as a strategy for change. One noted, “We believe that the best strategy …is to focus on developing more jobs, as well as the programs, services, and supports that people with I/DD need … The employment and services marketplace will evolve accordingly and unwanted employment options will fade from the scene.” (Arc of the US, 2011) Unfortunately, twenty years of employment outcome data has shown that this has not proven sufficient. Segregated facilities are entrenched and growing larger in the numbers of people served every day.

We need to acknowledge that this must change. This begins by recognizing that the segregated, facility-based approach will not simply fade away. There needs to be agency commitments to immediately end new referrals to segregated models and, secondly, put in place strategies to downsize facility-based models over a reasonable time span. These need to be part of Employment First.