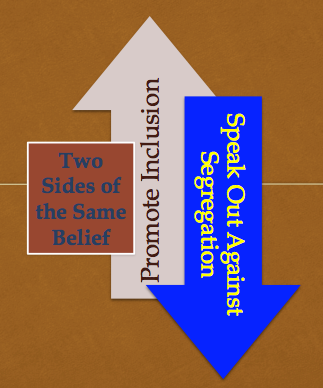

The Problem with Pro-Inclusion but Not Anti-Segregation

I am writing this post after providing a week’s worth of training to the staff of NOVA Employment, just outside of Sydney, Australia. This is my second visit to support the work of this agency “down under,” and I have a number of impressions to share.

I am writing this post after providing a week’s worth of training to the staff of NOVA Employment, just outside of Sydney, Australia. This is my second visit to support the work of this agency “down under,” and I have a number of impressions to share. The result of all this, in addition to valuing staff in other ways, is a productive agency that continually finds well-matched jobs for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, autism, and psychiatric disabilities.

The result of all this, in addition to valuing staff in other ways, is a productive agency that continually finds well-matched jobs for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, autism, and psychiatric disabilities.

I have always been a bit of a science geek. I find a sense of understanding about life, and even spirituality, from the deep discoveries we are making in the cosmos, particle physics, and quantum mechanics. And the pace of recent discoveries has been exhilarating. Just a few short years ago, we only knew of the planets in our own solar system. Now the number of identified planets is close to 800. This kind of thing alters the perception of our place in the universe.

What I also love about science is illustrated by the recent confirmation of the Higgs boson, a tiny particle that’s been theorized but never found. Without getting into a technical description, discovering or ruling out the Higgs would alter our fundamental understanding of how things are and how matter, including ourselves, exists. It is a monumental achievement in science.

But before the announcement of the Higgs, like any theory without evidence, there were conflicting scientific opinions. A group of respected physicists doubted the particle would ever be found, and believed that it likely didn’t exist.

But here is what happened. After a good deal of research, the particle was confirmed. So what did the scientists who had a different view do? Did they refuse to accept the results? No. They discarded their own carefully developed theories and embraced the new evidence. Basically they said, “We were wrong; let’s move on in a world where the Higgs exists.”

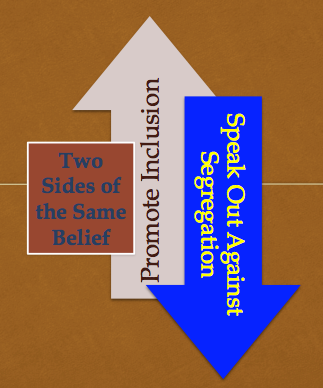

Now compare this to the evidence facing disability providers regarding segregated employment and sheltered workshops. Researcher Bob Cimera offered this succinct summary of a 2012 study: “…individuals from sheltered workshops earned less ($118.55 versus $137.20 per week), worked fewer hours (22.44 versus 24.78), and cost substantially more to serve ($7,894.63 versus $4,542.65) than peers who did not participate in sheltered workshops prior to become supported employees.”

Put another way, individuals who participate in sheltered workshops prior to becoming employed in the community via supported employment were “worse off than individuals who never participated in sheltered workshops.”

So, unless there is some contradictory evidence, wouldn’t it make sense to start planning a better way to fund day services than sheltered work? Yet, when this is proposed, the protesting roar of established providers has been loud. And it is based on their belief that “many people need a workshop; they are not productive enough to work in mainstream employment.” Well, where is the evidence? So far, all the research says that simply is not true.

Sheltered work doesn’t work – we have found our Higgs boson in the disability field, but most everyone still refuses to accept it.

Employment services are included in the integration mandate of the ADA! This recent ruling in Oregon by United States Magistrate Judge Janice Stewart is a huge landmark decision. It should cheer advocates who are working to slow and eventually end the growing numbers of people with disabilities needlessly spending their days in segregated sheltered workshops.

Similar to many states, most Oregonians with developmental disabilities in vocational services work in sheltered workshops, even though most would prefer to work in a real job. Each year, more are referred to these facilities. Sadly, this includes graduating students with disabilities – who should never need to see the inside of a workshop. This year a lawsuit spearheaded by Disability Rights Oregon was brought on behalf of 2300 individuals with disabilities in that state being needlessly kept away from real job opportunities. The suit charges that the state is violating the ADA by not providing employment services to people with disabilities in the most integrated settings appropriate. Now, the judge in the case has ruled that the plaintiffs can make such a claim under the ADA.

A legal basis for the suit was a previous Supreme Court decision known as Olmstead. Olmstead found that Title II of the ADA requires states to offer services in the most integrated setting possible, including shifting programs from segregated to integrated settings. Up to now, litigation under Olmstead has focused on supporting people in residential institutions to move to community settings. This has been followed by suits about other congregate settings such as nursing homes that claim to be community-based, but really serve as institutions, unnecessarily segregated people as well. Most recently, advocates have used Olmstead to challenge waiting lists and even state budget cuts. But this case is the first specific ruling regarding employment services and the integration mandate of the ADA.

In response to the suit, Oregon filed a Motion to Dismiss the case, saying that employment claims cannot be made under Title II of the ADA and that Olmstead does not apply to employment services. In her ruling, Judge Stewart stated “…this case does not involve ’employment,’ but instead involves the state’s provision (or failure to provide) ‘integrated employment services, including supported employment programs.'” The Judge thus affirmed that employment services is included in the integration referred to in the ADA, and gave the Plaintiffs time to file an amended complaint due to wording problems in the complaint, so further rulings are still to come on the case.

Oregon is just the tip of an iceberg. The state currently spends $30 million a year for individuals with disabilities to be in sheltered workshops – the lion’s hare of state vocational service dollars. With few exceptions, this is also true nationally. In NY, some estimates are close to a billion dollars spent for segregated day services. Yet, a 2010 study by Oregon’s own agency notes that cumulative costs generated by sheltered employees may be as much as three times higher than the cumulative costs generated by supported employees – $19,388 versus $6,618.”

Even though every state provides supported employment, on average these services represent only one of every five people served. Vastly more money is spent on segregation than on integration. And so far, most vocational service providers have responded by circling the wagons to protect their facilities. Most states do not even have an Olmstead plan related to phasing in more integrated employment services. Very few have any practical plan to reduce the population in sheltered workshops in a thoughtful way over time. Instead, there are vague goals of improving employment outcomes and little supporting funding. It seems that state money just keeps flowing to how and where it was spent previously, so real change never comes.

So maybe the time has finally arrived for us all to recognize the injustice of this. And apparently, it has taken a lawsuit to jump-start it. I say it’s about time.