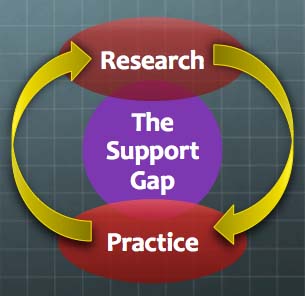

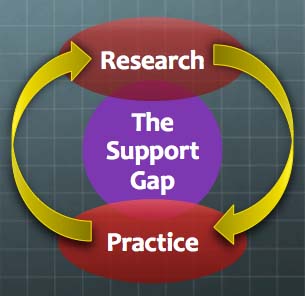

The Support Gap: Research to Practice and Back

Website: https://daledileo.com

Mr. DiLeo’s observations and conclusion are neither surprising nor should they be too troubling. The same could be said about hospitals, physician’s clinics, etc.: Different outcomes as a result of different clinical approaches/methods, equipment or other variables. In some ways, Mr. DiLeo’s post argues for more consistent information about what the outcomes are for different programs/agencies and greatly enhanced choice and self-determination in the selection of who/where one will obtain and receive their supports. I’d argue that this is the first thing to fix, the lack of accessible and meaningful information to make a better informed choice and/or the ability within a state’s structure to exercise choice in provider selection. To me these are way more basic than methodology to more uniformly measure and hold providers accountable to any particular set of outcomes. We all want what’s best. However, let’s not forget we all define best differently.

While I tentatively agree with you, Dale, I have some reservations. I think we all know the axiom “to every piece of research there is an equal and opposing piece of research”, and that should in itself provide a caution. And we need to be reviewing the research carefully. Just because something has been labelled “evidence-based”, we should not necessarily accept it at face. For example, research overwhelmingly shows that ABA approaches “work” for people with autism, but autistic folks who have experienced it are increasingly coming forward with objections and horror stories. Who is it we will listen to, the “experts” or the people who are most affected? I would like to see our field align more closely with the field of Critical Disability Studies. An analysis of power is central here, and much needed.

Anonymous

The delta between what we want to see take place in a person’s life and what actually takes place is at the crux of the issue. if we can reduce that delta people live better lives; how do we achieve that – training,consultation, values, pay, benefits, supervision, etc. if not, then we don’t ever achieve what we really want to see take place

jeff