Earlier this summer, the NBC’s news show, Rock Center, aired a critical examination of some Goodwill agencies paying workers with disabilities wages as low as 22 cents per hour. Some viewers responded with outrage; others defended the practice as necessary. Readers of this blog will know that I have presented several arguments as to why this practice is truly exploitive and must end. But the Goodwill scenario is particularly interesting because of its complexity. Let’s examine this recent media story more closely, as there are at least eight troubling issues being mixed together in this stew.

1. Extremely low wages for workers with disabilities.

The obvious one is the fact that many workers with disabilities earn next to nothing when sub-minimum wage is used. Why should we allow any employer, and particularly one charged with helping people with disabilities, to provide wages to them that are exempt from minimum wage? Goodwill offers some responses, and we will review these in turn below. But the basic issue is that the people most in need of income are the ones who are being severely shortchanged by the very agency supposedly helping them.

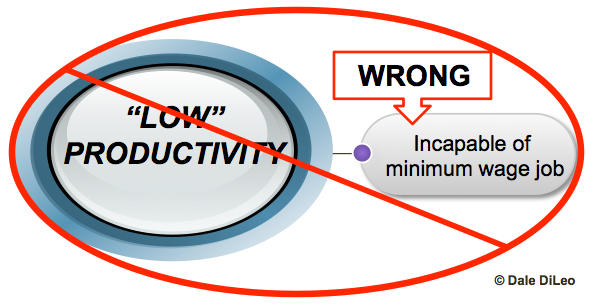

2. The false argument that without low wages, people wouldn’t be able to work at all.

Goodwill’s website notes the practice is a “tool” to help people get jobs “who otherwise would not have them.” On the Rock Center piece, Goodwill International Executive Director Jim Gibbons states that eliminating sub-minimum wages “would mean that many hard-working people would be out of their jobs.” This is only true if Goodwill abandoned those people if the sub-minimum wage was phased out. First, there is no research or other evidence to support people need sub-minimum wage to work. In fact, there is a lot of evidence to the contrary. Consider that at least 50 Goodwill affiliates do not elect to use sub-minimum wage, and many are quite successful at placing individuals with disabilities in minimum wage or better jobs. Beyond Goodwill, there are many examples of other agencies working with individuals with challenging disabilities and providing good job matches at good pay. With proper matching and support, people can be productive to merit minimum wage or better.

3. The wage disparity of non-profit management, their direct service staff, and the people they serve.

In 2011, the top five highest paid employees for Goodwill Industries of the Columbia Willamette (Oregon) made a combined total of $1,506,373 in salary and benefits. With this amount of money going to a few top staff, and at the same time the mission of the agency is stated as “to enhance the quality of life of the people we serve,” there is a severe mismatch of mission and results. A Watchdog.org analysis of the recent tax returns for 109 Goodwills that use the Special Wage Certificate found top executives were paid more than $53.7 million. Seventeen Goodwills reported executive compensation in excess of $1 million per year with 30 CEOs receiving more than $293,000 per year in total compensation. With excessive funding going to management salaries, it’s impossible to accept that the workers with disabilities (whom agencies exist to serve) should be subject to incredibly low wages, while doing ANY of the work that supports these executive salaries. This is the very definition of exploitation.

4. Excessive administration costs for serving people with disabilities.

Organizations that receive taxpayer funding to provide services should be held accountable for expenses and the outcomes produced. In this case, watchdog.org noted practices such as:

- 13 organizations spent more than $100,000 in annual conference expenses.

- One Goodwill tax return showed a CEO and his spouse were “entitled to first-class travel and access to a private club.”

5. Misleading marketing that equates donations with jobs.

Many Goodwills use expensive marketing, including billboards, media ads, and more to promote donations, equating the value of those donations with producing jobs for people with disabilities. Yet it is impossible to determine what percentage of donations actually goes to direct vocational services, and what wage outcomes are produced as a result. Certainly high worker wages are not a general result. If Goodwill wants to make advertising claims that say a donation directly results in a job, they should produce the evidence nationally. I would bet that for every $100 spent, less than $1 is paid in wages to a worker with a disability. It would be interesting to see how far under a dollar it really would be. Also troubling is that the marketing of donations paired with employment can produce a underlying message of charity being need for workers with disabilities. This harms national efforts in supported employment core marketing to business of productivity, not charity.

6. The simplistic assumption that for people with disabilities, “it’s not the money, it’s the fulfillment.”

On camera, Goodwill’s Jim Gibbons said it’s not about “livelihood, it’s about fulfillment.” Of course being productive and working is fulfilling. People work for many reasons, and not just for pay. And for those who have been historically kept out of the workforce, any job regardless of pay might seem good. But even if people need to learn about the concept of being paid fairly for work, that doesn’t mean they should be taken advantage of. In fact, exploitation includes paying people less when they haven’t learned or even care yet about the value of their work. Teach them. That’s part of your job.

7. The use of sub-minimum wage to shortcut quality job matching and support.

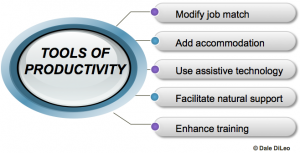

Providing quality employment services involves individualized planning and support to help people work in jobs well-matched to their skills and interests. Some Goodwill affiliates, and many other agencies like them, have their services flow in the opposite direction. They offer limited job choices, based more on their internal needs than the job applicants. For instance, regardless of Albert’s skills, here is a job in a retail environment selling used items. And when Albert is slow hanging up clothes, and his performance is not equal to expectations, cut his pay to match productivity, even if it is 22 cents per hour. This is inadequate for vocational service at any funding level. What about more training, accommodations, or a better-matched job? I have discussed this issue previously: The best predictor of job success is not whether people can work at lower standards for lower wages; it is how well we customize employment and provide job supports to meet productivity demands. Using sub-minimum wage is, at best, lazy, and under scrutiny, exploitive.

8. The social and self-identity ramifications of workers earning pennies or a few dollars per hour.

Something I have yet to see mentioned in the discussion of this topic is the social price paid when workers receive paychecks of less than a few dollars per week. What can this do to self-esteem and the perceptions of others in his or her social circle? It’s true that some folks might not be affected by their low paycheck, or care what others think of that, but in our society, greater income can lead to many more choices about housing, recreation, free time, and other important facets of society, not to mention pride. If the response is “that doesn’t matter” or “he/she doesn’t care,” then one must question how well people with disabilities and their families have been supported in understanding and building what is possible – the quality life potential in social environments when one earns a decent living, regardless of disability. Maybe if they don’t care, it’s because they haven’t had the experience of disposable income or have been taught the value of money. Maybe those CEOs who are expert in the importance of salary should be responsible for providing this training…

~

Each of these issues I’ve listed are deeply problematic. None are defensible either morally or as an evidence-based practice. And while state funding agencies and Congress debates, CEOs bring home huge salaries, benefits and perks, while workers with disabilities are kept in poverty, supposedly because 1) they have a “choice” and 2) without enforced poverty, they wouldn’t be working at all. Hogwash. We need to end all of these shameful practices and phase out sub-minimum wages.