The state of Oregon, like it or not, will have a spotlight shining on it as it plans the future of employment services for people with intellectual/developmental disabilities (ID/DD). Like most states, Oregon spends the large majority of its employment service dollars ($30 million a year) for individuals with disabilities to be in sheltered workshops. In 2012, advocates filed a class action lawsuit challenging Oregon’s failure to provide supported employment services.

Last month, in a startling move, the US Department of Justice (DOJ) announced it had joined the lawsuit, stating, “We are seeking to represent the interests of Oregonians currently working in sheltered workshops and those who are at risk of being placed in sheltered workshops upon their graduation.”

The complaint gave many examples of how people are currently “working” in workshops, such as one where 150 people with disabilities hand sort trash and clean garbage bins, with some earning only 44 cents an hour. The complaint noted that these conditions have persisted for decades, despite repeated reports and plans calling for action for reform. Again, this type of work is not unique to Oregon, and can be found throughout the US.

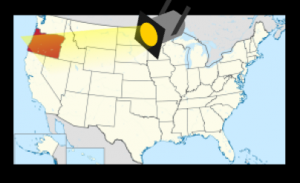

|

| State Data: The National Report on Employment Services and Outcomes, ICI, UMass Boston |

Also, nearly every state reports integrated employment as only a small part of their day services. A recent article from the Institute on Community Inclusion at UMass Boston concluded that less than one in five people nationally are provided supported employment services, and that “there has not been a meaningful change in the number of people with ID/DD in integrated employment since 2001.”

In response to the complaint and the weight of the DOJ joining, Oregon Governor Kitzhaber issued an Executive Order to stop funding work assessments in sheltered workshops in 2014, and to stop funding sheltered workshops for those coming out of school or not already in one.

The Good

Every service system serves more people each year, yet the percentage of people in the majority service, sheltered work, stays the same. In effect, the numbers of people entering segregated work grows larger than those entering integrated work. In other words, four times as many people enter sheltered work each year as integrated work, making the problem larger and more difficult with time.

The Oregon executive order effectively freezes new placements in sheltered workshops, ending their continued growth. In addition, by eliminating work assessments in workshops, the order acknowledges the work being done there has little to no validity for predicting vocational preference or competence for any individual.

The state also says it will establish and implement a policy that Employment Services shall be evidence-based and individualized. Over the next nine years, the state sets targets to provide job services to 2,000 individuals.

The Bad

The Order considers group employment of eight or less, including crews and enclaves (an antiquated definition of supported employment) to be “integrated employment settings.” Group employment models have serious issues, and are not considered best practices, nor are they individualized as the Order announces services should be. Treating group placements as successful vocational outcomes misses an important point.

The Ugly

Disability Rights Oregon (DRO) immediately noted the planning holes in the Order regarding the future of the workshops in the state. Although “a significant reduction over time of state support of sheltered work” is stated, DRO notes that it provides “no adequate or effective commitment to benchmarks, system outcomes, or re-allocating or re-distributing resources to provide individuals with disabilities access to employment services in integrated settings. In sum, the plan all but assures that the goals for delivering services to individuals in the community are advisory goals and not commitments.”

This means there is little realistic planning for the challenging process to transfer to real community jobs those workers already placed in segregated facilities earning sub-minimum wages. And, according to the benchmarks, probably only a third of those already placed there will have access to employment serves over the next decade. Systems change requires a stronger effort in moving people out of workshops, not just closing the door to get in. It’s like trying to end institutionalization by simply stopping intakes. That’s not really a process, it’s more just a waiting game, and gives up on the residents already there.

Although this Executive Order acknowledges the goal of increasing employment and decreasing segregated work, as the system continues to grow, in all likelihood, most workers still stuck in sheltered facilities will continue to have no other options during their lifetime.