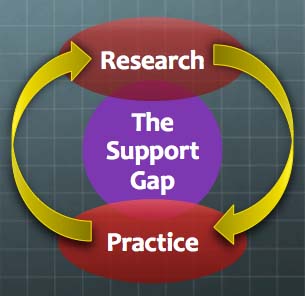

The Support Gap: Research to Practice and Back

I am writing this post after providing a week’s worth of training to the staff of NOVA Employment, just outside of Sydney, Australia. This is my second visit to support the work of this agency “down under,” and I have a number of impressions to share.

I am writing this post after providing a week’s worth of training to the staff of NOVA Employment, just outside of Sydney, Australia. This is my second visit to support the work of this agency “down under,” and I have a number of impressions to share. The result of all this, in addition to valuing staff in other ways, is a productive agency that continually finds well-matched jobs for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, autism, and psychiatric disabilities.

The result of all this, in addition to valuing staff in other ways, is a productive agency that continually finds well-matched jobs for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities, autism, and psychiatric disabilities.

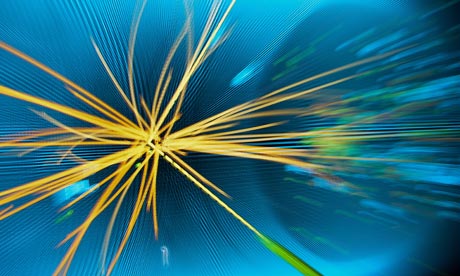

I have always been a bit of a science geek. I find a sense of understanding about life, and even spirituality, from the deep discoveries we are making in the cosmos, particle physics, and quantum mechanics. And the pace of recent discoveries has been exhilarating. Just a few short years ago, we only knew of the planets in our own solar system. Now the number of identified planets is close to 800. This kind of thing alters the perception of our place in the universe.

What I also love about science is illustrated by the recent confirmation of the Higgs boson, a tiny particle that’s been theorized but never found. Without getting into a technical description, discovering or ruling out the Higgs would alter our fundamental understanding of how things are and how matter, including ourselves, exists. It is a monumental achievement in science.

But before the announcement of the Higgs, like any theory without evidence, there were conflicting scientific opinions. A group of respected physicists doubted the particle would ever be found, and believed that it likely didn’t exist.

But here is what happened. After a good deal of research, the particle was confirmed. So what did the scientists who had a different view do? Did they refuse to accept the results? No. They discarded their own carefully developed theories and embraced the new evidence. Basically they said, “We were wrong; let’s move on in a world where the Higgs exists.”

Now compare this to the evidence facing disability providers regarding segregated employment and sheltered workshops. Researcher Bob Cimera offered this succinct summary of a 2012 study: “…individuals from sheltered workshops earned less ($118.55 versus $137.20 per week), worked fewer hours (22.44 versus 24.78), and cost substantially more to serve ($7,894.63 versus $4,542.65) than peers who did not participate in sheltered workshops prior to become supported employees.”

Put another way, individuals who participate in sheltered workshops prior to becoming employed in the community via supported employment were “worse off than individuals who never participated in sheltered workshops.”

So, unless there is some contradictory evidence, wouldn’t it make sense to start planning a better way to fund day services than sheltered work? Yet, when this is proposed, the protesting roar of established providers has been loud. And it is based on their belief that “many people need a workshop; they are not productive enough to work in mainstream employment.” Well, where is the evidence? So far, all the research says that simply is not true.

Sheltered work doesn’t work – we have found our Higgs boson in the disability field, but most everyone still refuses to accept it.

Employment services are included in the integration mandate of the ADA! This recent ruling in Oregon by United States Magistrate Judge Janice Stewart is a huge landmark decision. It should cheer advocates who are working to slow and eventually end the growing numbers of people with disabilities needlessly spending their days in segregated sheltered workshops.

Similar to many states, most Oregonians with developmental disabilities in vocational services work in sheltered workshops, even though most would prefer to work in a real job. Each year, more are referred to these facilities. Sadly, this includes graduating students with disabilities – who should never need to see the inside of a workshop. This year a lawsuit spearheaded by Disability Rights Oregon was brought on behalf of 2300 individuals with disabilities in that state being needlessly kept away from real job opportunities. The suit charges that the state is violating the ADA by not providing employment services to people with disabilities in the most integrated settings appropriate. Now, the judge in the case has ruled that the plaintiffs can make such a claim under the ADA.

A legal basis for the suit was a previous Supreme Court decision known as Olmstead. Olmstead found that Title II of the ADA requires states to offer services in the most integrated setting possible, including shifting programs from segregated to integrated settings. Up to now, litigation under Olmstead has focused on supporting people in residential institutions to move to community settings. This has been followed by suits about other congregate settings such as nursing homes that claim to be community-based, but really serve as institutions, unnecessarily segregated people as well. Most recently, advocates have used Olmstead to challenge waiting lists and even state budget cuts. But this case is the first specific ruling regarding employment services and the integration mandate of the ADA.

In response to the suit, Oregon filed a Motion to Dismiss the case, saying that employment claims cannot be made under Title II of the ADA and that Olmstead does not apply to employment services. In her ruling, Judge Stewart stated “…this case does not involve ’employment,’ but instead involves the state’s provision (or failure to provide) ‘integrated employment services, including supported employment programs.'” The Judge thus affirmed that employment services is included in the integration referred to in the ADA, and gave the Plaintiffs time to file an amended complaint due to wording problems in the complaint, so further rulings are still to come on the case.

Oregon is just the tip of an iceberg. The state currently spends $30 million a year for individuals with disabilities to be in sheltered workshops – the lion’s hare of state vocational service dollars. With few exceptions, this is also true nationally. In NY, some estimates are close to a billion dollars spent for segregated day services. Yet, a 2010 study by Oregon’s own agency notes that cumulative costs generated by sheltered employees may be as much as three times higher than the cumulative costs generated by supported employees – $19,388 versus $6,618.”

Even though every state provides supported employment, on average these services represent only one of every five people served. Vastly more money is spent on segregation than on integration. And so far, most vocational service providers have responded by circling the wagons to protect their facilities. Most states do not even have an Olmstead plan related to phasing in more integrated employment services. Very few have any practical plan to reduce the population in sheltered workshops in a thoughtful way over time. Instead, there are vague goals of improving employment outcomes and little supporting funding. It seems that state money just keeps flowing to how and where it was spent previously, so real change never comes.

So maybe the time has finally arrived for us all to recognize the injustice of this. And apparently, it has taken a lawsuit to jump-start it. I say it’s about time.

Controversy continues regarding efforts around the country to close large state-run institutions for people with developmental disabilities. Many of these recent closure announcements have more to do with excessive costs (which are absurdly high) in tough budget times, combined with an ongoing inability to end serious abuse and neglect, as reported in the media in various locations.

Controversy continues regarding efforts around the country to close large state-run institutions for people with developmental disabilities. Many of these recent closure announcements have more to do with excessive costs (which are absurdly high) in tough budget times, combined with an ongoing inability to end serious abuse and neglect, as reported in the media in various locations.Both of those issues are of course serious instigators for institutional closure, but they are really symptoms of the true problem. The most compelling issue by far is that the support that can be provided at such facilities is inadequate, segregated from our society, and obsolete, when compared to the life quality and individualized support that can be offered in small, local community settings. The associated costs and abuse and negligence at institutions are outgrowths of a model that is badly flawed. No amount of video monitoring, quality assurance controls, new or rebuilt structures, or other measures can fix the fundamental problem.

In response, some families fall back on the “choice” argument (“we should have the option of knowing what’s best for our child, including institutionalization…”), which I can empathize with, but have discussed elsewhere in this blog as not being a sound argument. Others talk about the impact moving out would have on individuals. This is, of course, important, and the experiences in other states must be used to learn how to minimize any negative impact.

Also, there must be a community support system to move to that is functional and effective. None of this is easy, but all these issues are solvable, and don’t change the need for closure. We know this because a dozen other states have accomplished full state-wide closure reasonably successfully. There remain problems in some community settings to be sure, but they are a different set of problems on smaller scales with more individualized solutions.

But I want to put that complex discussion aside for a moment, and focus on the reactions of one key group to announcements of planned institutional closure – the employees who work there. This is the institutional staff; state employees, who, I’m sure, are caring people. Despite their compassion, they naturally view a facility closure through one lens, that of personal job loss.

As a result, their employee unions have reacted to announcements of intentions to close a facility with protest rallies. They have released scary statements regarding the huge economic impact their job loss will have on local communities. They are doing their mission to protect jobs, thus working hard to stop plans for moving people out and closing the center. Yet, there is a bigger picture – let’s consider this for a moment.

Certainly a significant job loss in any community is cause for concern. There would need to be steps taken to support transfers into other public sector positions, and provide for re-training and job placement. Job downsizing should come in stages whenever possible. But let’s get this straight. Public sector job loss is not the core priority when deciding whether an institution should close, nor should it be. What should be central at all times is what is the best we can do for those people living in institutions.

Unfortunately, state governments don’t always seem to weigh these factors in this way. In NJ, a task force is now reportedly reviewing closure plans based on several concerns. One is “the economic impact on the community in which the developmental center is located if that center were to close.” A second is “projected repair and maintenance costs of the center.”

These are considerations for planning how to do the closure, not for whether there should be one. That decision should be based firmly on one thing, and one thing only: What is best for the people that live there. Job security just does not stand equal to that. And in any informed discussion of service design, the evidence for quality service all points to community life with customized support.

If you ignore this central fact, and then untangle the arguments, what you have left is a group of vulnerable people kept in an unnecessary, obsolete, and potential harmful environment, so those who work there can continue in their jobs. How is this different from keeping people hostage to maintain a local economy?

Not only that, spending on institutions comes at a cost; this is taxpayer money that could be spent on improving and expanding needed community-based disability services, now burdened with wait lists, understaffed, and with inadequate training. If you were to set your spending priorities from scratch, there is nothing, and I mean nothing, that supports spending money on keeping people in facilities rather than supporting them in the community.

Yet, in Illinois, the state union, AFSCME, is fighting hard to prevent the Jacksonville Developmental Center from closing, sending letters to lawmakers and holding public protests.

In NJ, the announcement of the planned closure of the Vineland Center has caused a storm of controversy and protests (see above photo) from public union officials and workers.

In one NJ news report, a union official “pointed out that the elimination of over 1,400 jobs in a county with rampant unemployment would bring local businesses and the entire community down.” That statement was followed by the comment, “We’re not here just to collect a paycheck, we’re here because we care.”

I’m sure that union official truly believes that. But for it to be meaningful, one should do some research into what we have learned these last twenty years about serving people in non-segregated environments. That pairing of “we care” with “job loss” implies those issues are partners.

But if you really cared about what’s best for the people you supposedly work for, than you’d be protesting their continued needless isolation from society, not your paycheck.